Photos from Turkey

| Home | About | Guestbook | Contact |

TURKEY - 1973-2015

A short history of Turkey

The Republic of Turkey is a country that is located mainly in Western Asia, with a smaller portion on the Balkan Peninsula in Southeast Europe. The Asian part is known as Anatolia or Asia Minor and shares a border with Georgia, Armenia, the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan, Iran, Iraq and Syria. The capital of Ankara is situated in its centre. The European part, Eastern Thrace, is separated from Anatolia by the Sea of Marmara, the Bosphorus strait and the Dardanelles. It shares a border with Bulgaria and Greece. Here is Turkey’s largest city, the former capital of İstanbul, straddling the Bosporus. Turkey now occupies an area of 783,356 km², and has a population of a little over 82 million people.

Anatolia is one of the oldest permanently settled regions in the world. In its south-east, near the Syrian border, is Göbekli Tepe, the site of the earliest known man-made religious structure; it was a temple dating to circa 10,000 BCE. Çatalhöyük, in southern Anatolia, is the site of a substantial settlement that existed between 7500 and 5700 BCE. Around 2300 BCE Indo-European people had migrated out of the Eurasian steppe and settled in Anatolia, gradually absorbing the native Hattian and Hurrian peoples. They spoke, now extinct, Anatolian languages. Best known is those of the Hittites, who established an empire around 1600 BCE centred on Hattusa (near modern Boğazkale, 200 kilometres east of Ankara) in north-central Anatolia. The Hittite Empire reached its greatest extent during the mid-14th century BCE and occupied almost all of Anatolia and parts of present-day Syria. The Hittite empire collapsed around 1180 BCE, and another Indo-European people, the Phrygians, then dominated Anatolia. Phrygia was destroyed in the 7th Century BCE by the Cimmerians, a nomadic Indo-European people. Western Anatolia was dominated by the Kingdom of Lydia and the regions Caria and Lycia, until 546 BCE, when the Persian Achaemenid Empire conquered all of modern-day Turkey.

The coast of Anatolia had become a place for settlement by Greeks, staring around 1200 BCE. The belonged to the Aeolian and Ionian tribes, two of the four major Greek tribes. They founded cities like Ephesus Smyrna (now İzmir) and, in 657 BCE, Byzantium - the latter Constantinople, now İstanbul. In 499 BCE the Greek city states on the coast of Anatolia rebelled against the rule of the Persian Empire, starting the Greco-Persian Wars, lasting fifty years. Alexander the Great of Macedon marched into Anatolia in 334 BCE, to free Greeks from Achaemenid rule and he continued to defeat the Persian Empire. After his death in 323 BCE, Anatolia was divided into a number of small Hellenistic kingdoms and the local Anatolian languages and cultures were gradually replaced by Greek language and culture. In the mid-1st Century BCE Anatolia was absorbed by the Roman Republic, although up to the 3rd Century CE parts were contested between the Romans and the Parthian Empire to the east.

Christianity gained a foothold in present-day Turkey in Antioch (now Antakya, in Hatay Province, between Syria and the Mediterranean) - the New Testament asserts that the name “Christian” first emerged here. By the 4th Century BCE, it had spread throughout the Roman Empire, and Constantine I (272 - 337 CE) became the first Christian Emperor. In 324, he chose Byzantium, an ancient Greek colony, to be the new capital of the Roman Empire. First described as “New Rome”, it became known as Constantinople (now İstanbul), named after the emperor. After the permanent division of the Roman Empire Constantinople became the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, later named by historians as the Byzantine Empire. It ruled most of present-day Turkey until the Late Middle Ages. Until the first half of the 7th Century, however, the eastern parts were contested by the Sassanid Empire, the successors to the Parthian Empire and the last Iranian Empire before the rise of Islam.

In the 11th Century the Qynyk (Kınık) branch of the Oghuz (Oğuz) Turks, a western Turkic people, started migrating from central Asia (roughly modern Kazakhstan) to the west. Their leader was Seljuq, a clan leader who had converted to Islam around 985. They migrated into mainland Persia and defeated the Ghaznavid Empire, a Persian Muslim dynasty, also of Central Asian Turkic origin. The Seljuks founded the Great Seljuk Empire and also adopted Persian culture and used the Persian language. In the latter half of the 11th Century, the Seljuk Turks began penetrating medieval Armenia and the eastern regions of Anatolia. In 1071, the Seljuks defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert, an Armenian town (now Malazgirt, in eastern Turkey). In the battle, the Seljuk sultan Alp Arslan defeated and captured Emperor Romanus Diogenes. This victory started the ethnic and religious transformation of Armenia and Anatolia. In 1077 the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum was established in parts of Anatolia conquered from the Byzantine Empire. It expanded until 1243 when the Mongols defeated the Seljuk armies at the Battle of Köse Dağ, a location between Erzincan and Gümüşhane. Vassals of the western Mongolian Ilkhanate, the Seljuk state ceased to exist after the last Sultan, Mesud II, was murdered in 1308.

The former Seljuk state broke up into various Turkish principalities, known as the Anatolian Beyliks. One of those, in the region of Bithynia, north-west Anatolia, was governed by Osman I. He ruled his small principality from what is now the town of Söğüt, from 1299 until his death in 1323 or 1324. He was the founder of what would be called the Ottoman dynasty and over the next 200 years Osman I’s small principality would evolve into the mighty Ottoman Empire. Osman’s son, Orhan, captured Bursa in 1326, making it the new capital of the Ottoman state and supplanting Byzantine control in the region. They captured Thessaloniki from the Venetians in 1387 and won the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, defeating the Serbs and opening the way into Europe. In 1453 Sultan Mehmed II conquered Constantinople: he was henceforth called Fatih Sultan Mehmet (Mehmed the Conqueror), bringing an end to the Byzantine Empire. Ottoman rule expanded and reached its peak in the 16th Century. Under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent most of the Middle East, North Africa and the Balkans as far north as most of Hungary came under his rule. His conquests came to an end at the Siege of Vienna in 1529.

The Ottoman Empire started to decline from the second half of the 18th Century; in the 19th Century attempts were made at reforms to modernise the state, but the country slowly started to unravel. Serbia became a self-governing monarchy in 1817 and Greece an independent republic in 1821. The Crimean War of 1853-1856 was part of a contest between major European powers for influence over territories of the declining Empire. There were numerous uprisings in the Balkans, like in Bulgaria and Macedonia, both cruelly suppressed. After the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 and the Congress of Berlin, the Ottoman Empire lost control in most of Europe, and in 1882 the British occupied Egypt. Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who ruled from 1876 to 1909. He was the last Sultan to have effective control over his fracturing country. He had suspended the constitution in 1876, but in 1908 a revolution by the Young Turk movement restored it and ushered in multiparty politics. They deposed him the following year. Abdul Hamid II was nicknamed abroad the ‘Red Sultan’ or ‘Abdul the Damned’, because of the massacres of Armenians and Assyrians during his rule and use of the secret police to silence dissent. His successor Sultan Mehmed V (ruled 1909-1918) became a figurehead, without real power. Under his rule, Turkey lost its remaining territory in North Africa (present-day Libya) to Italy and all its European regions, except a strip of land west of İstanbul. It led in 1913 to a coup d‘état in which the government fell into the hands of a triumvirate known as the “Three Pashas”.

When the First World War broke out, the remnants of the Ottoman Empire allied itself with the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria), but, with them, it eventually faced defeat. During the war the Armenian population was systematically exterminated. On 24 April 1915 Armenian intellectuals and community leaders were rounded up from Constantinople, initially deported to the region of Angora (now Ankara), murdered, or subjected to forced labour. There was the wholesale killing of the able-bodied male population. Women, children, the elderly and infirm were deported on death marches to the deserts of Syria, deprived of food, water, and subjected to robbery and rape by their military escorts. The Armenian Genocide has been documented in great detail, also by contemporary Turkish witnesses, but until this day, the Turkish government refuses to acknowledge it. It is one of the first modern genocides, but it wasn’t the only one perpetrated by the Turks during the First World War. Assyrian or Syriac Christians in eastern Turkey were also forcibly relocated and massacred by the Ottoman army. Greeks in Anatolia were also systematically killed and suffered death marches, expulsions, arbitrary execution and the destruction of Eastern Orthodox cultural and religious monuments. By late 1922 most Greeks in Asia Minor had either fled or had been killed. Almost all who remained were exchanged in 1923 for Turks residing in Greece.

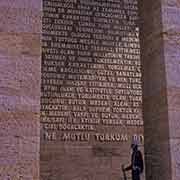

The victorious Allied powers occupied Constantinople (İstanbul) in 1918 and on 10 August 1920 the Treaty of Sèvres was signed between the Allies and the Ottoman Empire. The Empire was dismembered, and it lost all non-Turkish territory. The treaty caused great resentment amongst Turks and prompted the establishment of the Turkish National Movement in Angora (Ankara). Its leader was Mustafa Kemal Pasha, who had distinguished himself as a military commander in the Battle of Gallipoli (1915-’16). He proclaimed a Government of the Grand National Assembly in 1919 and assumed command in the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923). This war, between the Turkish National Movement and the allies, aimed to revoke the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres. On 23 April 1920, the Ankara-based regime declared itself the legitimate government of the country and abolished the Sultanate on 1 November 1922. The Treaty of Lausanne of 24 July 1923 led to international recognition of a “Republic of Turkey”, and on 29 October 1923, the republic was officially proclaimed in Ankara, the country’s new capital. Mustafa Kemal became the republic’s first President and introduced reforms that aimed to make Turkey a modern parliamentary democracy under a secular constitution. In 1934 the government passed a law requiring all citizens to adopt the use of hereditary, fixed, surnames. The Turkish Parliament then bestowed upon Mustafa Kemal the honorific surname “Atatürk” (Father Turk).

Atatürk died on 19 November 1938 and was succeeded by İsmet İnönü. After the Second World War, in which Turkey had remained neutral, only joining the Allies at the very end, the country became a charter member of the United Nations. In 1946 it became a multiparty democracy, although this was interrupted by military coups in 1960, 1971, and 1980. Turkey had joined NATO in 1952, and 1974 invaded Cyprus after a coup on the island had installed a regime that wanted to unite with Greece. It declared on the northern part of the island the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus; this has not been recognised by any country, except Turkey. In 1978 the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) was established, and since 1984 the Kurds have demanded either independence or greater autonomy with political and cultural rights. To no avail: the PKK has been declared a terrorist organisation, and the Kurds subjected to repression. More than 40,000 have died, villages destroyed, Kurdish journalists, activists and politicians “disappeared “. On 15 July 2016, an unsuccessful coup attempt tried to oust the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Since then his government has imposed censorship on the press and social media, locked up numerous journalists, blocked sites such as YouTube, Twitter and Wikipedia and has turned away from the secular tradition of modern Turkey’s founder Kemal Atatürk, moving in a more conservative Islamist and authoritarian direction. Negotiations for membership of the European Union are on hold: the European Court of Human Rights and many other international human rights organisations have condemned Turkey for thousands of human rights abuses.