Photos of The Edge of the Kalahari, Botswana

The Edge of the Kalahari

A road leads northwest from Molepolole, the capital of the Kweneng District, to the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, passing, after 75 kilometres through Letlhakeng, with about 6,000 people, and 30 kilometres further on through Khudumelapye, a small village with less than 2,000 inhabitants. The people are mostly Bakwena, but many speak Se-Kgalagadi - a language distinct from standard Setswana (here called Se-kwena). The name Kgalagadi, meaning “a waterless place” in Setswana, is the origin of “Kalahari”. It is usually referred to as a desert. Still, it is instead a large semi-arid sandy savanna extending for 900,000 km² in Southern Africa, covering about 70% of Botswana and parts of Namibia and South Africa.

you may then send it as a postcard if you wish.

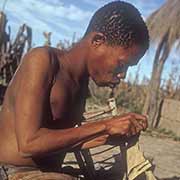

The San (or Bushmen) people lived in the Kalahari for 20,000 years as hunter-gatherers, hunting wild game with bows and poisoned arrows and gathering edible plants, like berries, melons and nuts, as well as insects. They got most of their water from plant roots and desert melons found on or under the desert floor, storing water in the blown-out shells of ostrich eggs. Their ancestors lived initially all over southern Africa with the Khoi peoples, as numerous caves adorned with “Bushman paintings” attest. Speaking languages collectively known as Khoisan, distinguished by the significant number of clicks in it, they were gradually driven from more fertile lands by migrating Bantu tribes to the wastes of the Kalahari. But progressively, the San, called Basarwa by the Tswana (a term meaning “those who do not rear cattle”), have been driven from their lands, forced into farming and staying in more permanent settlements. One of those was Matipatsela, a few kilometres to the south of Khudumelapye and another, with the same family, Tsesane, about 20 kilometres northwest of the village. The people no longer could practice their hunting-gathering life. Government programs have been implemented without their participation. Missionaries of all stripes have come to convert them: the people at Tsesane and Matipatsela had been converted to the Bahá’í Faith!

Many indigenous San people have now been forcibly relocated from their land onto reservations, where minimal prospect of employment exists, and alcoholism is rampant. In 1996, the De Beers Company evaluated the potential of diamond mining at Gope, in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. The Government of Botswana granted a permit to De Beers’ Gem Diamonds/Gope Exploration Company (Pty) Ltd. to conduct mining activities within the reserve. In 1997, the eviction of the San and Bakgalagadi tribes in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve from their land began. To make them relocate, they have been denied water from their land and faced arrest if they hunted, which was their primary food source. Although their lands lie in the middle of the world’s richest diamond field, the Government denied any link to mining. It claimed it was done to preserve the wildlife and ecosystem, even though the San people had lived sustainably on the land for millennia. But in 2006, a Botswana High Court ruled in favour of the San and Bakgalagadi tribes in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, claiming their eviction from the reserve was unlawful.